THE MAN WHO NEVER STOPS

Robert Caro Has Focused the Last Fifteen Years on Lyndon Johnson and

Changed the Nature of Political Biography

By Stephen Harrigan

“I seem to remember shaking his hand.” Robert A. Caro spoke in a voice so suddenly soft and musing that he appeared to have gone into a trance. "That's really strange," he said, sitting back on the couch and thoughtfully stroking his necktie. "Until you asked me that just now, I'd totally forgotten. But I think I may have shaken his hand."

It was during the 1964 presidential campaign that Caro saw with his own eyes the smothering, grasping, gigantic figure who would ultimately, from beyond the grave, commandeer decades of Caro's life and thought. Lyndon Johnson was campaigning in New England, and Robert Caro, a young Newsday reporter on urban politics, had been reassigned to cover him.

"I was a substitute," Caro recalled. "I was nothing. I was never part of the pool. I was never on the plane. I could only see him from a distance. But what got me was this colossal energy. It was an endlessly long day-he was always jumping out of the car, constantly shaking hands.

"We were in New Hampshire. During that day or the day before, Teddy Kennedy had been in a plane crash and hurt his back. In my memory, it was midnight when Johnson decided to go to Boston and visit him. So a few hours later, we were standing outside the hospital in the dark. There were people in hospital uniforms standing over on this side waiting to shake his hand, and the press standing outside the was lined up over here. Then he came out, looming, untired. I remember seeing his hands. They were scratched and bleeding! Whether I just saw him shaking hands with the nurses or whether he actually came over to me, I can't tell you. But I was close enough to see his hands bleeding."

Caro was silent for a moment, then snapped out of it. The man who has tirelessly invaded Lyndon Johnson's secret motivations for fifteen years is himself cunningly private, and such moods of introspection are rare. He talks with passion and an undisguised sense of achievement about his vivid, ongoing biography of L.B.J., but you can't get him to brood on it. His life of Johnson, he says, began as an exploration of "how political power works in a democracy on a national scale," but the work thus far is so personal, so full of awe and outrage toward its main character, that its origins might lie not just in intellectual curiosity but in the faint memory of a bloody handshake.

On the February morning I sat talking with Caro in his apartment on Central Park West, Means of Ascent, the second of a projected four volumes of Top Rep. Johnson, The Years of Lyndon Johnson, was nearing publication. Caro, at fifty-three, was halfway through. Over the previous few months, The New Yorker had published six excerpts, and Alfred A. Knopf, Caro's publisher, had just sent out bound sets of galley proofs to reviewers, along with a publicity sheet that reminded them of the lavish praise they had bestowed on volume one ("Stands at the pinnacle of the biographer’s art"; "By every measure ...a masterpiece").

Caro, already well into volume three, appeared bright-eyed and eager, neither exhausted by his labors nor haunted by the ghost of his spectacular subject. I looked in vain for the usual fetishes with which writers surround themselves, but there were no photographs or hokey plaster busts of L.B.J. anywhere. Indeed, except for the framed awards hung discreetly in aback hallway-the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, the National Book Critics Circle Award-there was no visible reference to Caro's obsessive occupation. The apartment's decor was elegantly spare. On the walls were nineteenth-century French landscapes that Caro and his wife, Ina, had collected on their annual vacations in France. The uncluttered bookshelves held leather-bound sets of the works of Tolstoy, Gibbon, and James Fenimore Cooper.

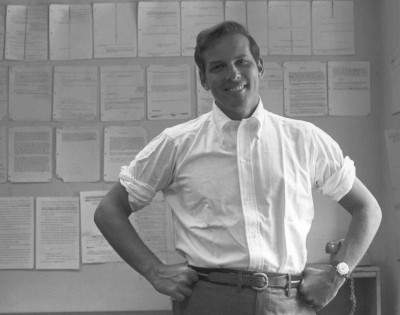

Caro himself, standing now with his elbows propped on the marble mantelpiece, was no disheveled bookworm. He was trim and donnish, with dark brown hair and dark brown tortoise-shell glasses, but the classy exterior did not conceal his revving energy. More eager to ask questions than to answer them, he appeared both gregarious and secretive.

When I asked him why his biography of Johnson-originally planned for only three volumes-was taking so long, he said in a genteel Manhattan accent, "I believe that time equals truth.

"I like being a reporter," he explained, "but there was one aspect of it that I truly hated. I never had enough time to really find out everything I thought I should know. I wanted to explore something all the way to the end."

One of the reasons for Caro's success is his inspired distaste for deadlines. He works seemingly without regard for the ticking of the clock or the passing of the years, and his relentless research into the life and times of Lyndon Johnson has generated its own legend. Already enshrined in Texas literary folklore is the image of Bob Caro, in his blazer and regimental tie, arriving at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, in Austin, and gazing upward with epic resolve at a four-story display of red archive boxes containing thirty-four million documents. Or Caro spreading his sleeping bag under the Hill Country sky to better understand the frontier isolation of Johnson’s background ("You'd wake up in the morning," he said, "and there was still nobody there !").

Caro and Ina, a medieval historian who aided him greatly in his research, spent a total of more than four years in Texas, poring over the documents in the L.B.J. Library, interviewing hundreds of Johnson’s contemporaries, and aggressively absorbing the landscape. In volume one, Caro's dogged methodology resulted not only in an unforgettably caustic portrait of Lyndon Johnson but also in set pieces of startling clarity and surprise. He took, for instance, what should have been the most boring subject on earth-the advent of rural electrification-and turned it into a chapter called "The Sad Irons," which may be the most brilliant single passage of prose ever written about Texas.

"What's most remarkable about Bob Caro," says Robert Gottlieb, who edited Caro's books at Knopf and continues to do so even though he is now editor of The New Yorker, "is the depth, the obsessiveness, the accuracy of his research. The totalness of it. He simply never stops. He simply finds out more than anybody else finds out about anything. And then, out of the infinite detail he accumulates, he creates real drama."

It was not only Caro's research that made his first volume on Johnson, The Path to Power, such a success when it was published in 1982. It was also the furrowed-brow grandeur of his prose, his gift for making the sluggish currents of modern political history roar along like a flash flood. His portrait of Johnson is meticulous but hardly temperate. This is not just a biography but a seething, emotional story about a man who, in Caro's words, had "a seemingly bottomless capacity for deceit, deception, and betrayal."

Johnson loyalists greeted Caro's depiction with a collective howl of outrage; and academic historians, while as agog as everyone else at Caro's narrative power, tsk-tsked what they perceived as the book's distortions and pumped-up drama.

But 450,000 readers bought The Path to Power. Its aims were clearly so mighty, its scope so audacious, that it became, if not the last word on Johnson, certainly the most compelling. For Texans, especially, The Path to Power filled avoid in a notoriously spotty historical record. This was not just the story of the rise of Lyndon Johnson; it was by default the basic text of the history of modem Texas.

The second volume of The Years of Lyndon Johnson is a hefty monument itself, though it is shorter than the first volume by about four hundred pages. Whereas The Path to Power is a panoramic survey of Johnson's life from his birth to his defeat by W. Lee

"Pappy" O'Daniel for the U.S. Senate in 1941, Means of Ascent is a concentrated study of "a seven-year period in the life of Lyndon Johnson in which his headlong race for power was halted."

Caro warns in his introduction that there were two "threads," one bright and one dark, running through the fabric of Johnson's personality and that in this volume, "the bright one is missing." Here L.B.J. is depicted as a villain of almost Shakespearean dimensions: weaseling out of active service in World War II and then shamelessly inflating his one combat experience; abusing his congressional power to acquire a marginal radio station and turn it into a major source of enrichment and influence peddling; and then finally-in a sustained narrative, told with the bold, sweeping strokes of a novel-stealing the 1948 Senate election from Coke R. Stevenson, a former governor of Texas and "old-style cowboy knight of the frontier" whose own threads, as Caro portrays him, were blindingly bright.

"It's not a question of liking him or hating him," Caro said of Johnson. "What I meant to do was understand him. People are going to say when the third volume comes out, 'Caro's view changed. Lyndon Johnson is now a hero.' Well, that's not the case. The case is, he's going to do heroic things. We wouldn't have a substantial amount of the civil-rights legislation we have today, for instance, if it hadn't been for Lyndon

Johnson. But the personality does not basically change. Anyone who expects a great personality change in Lyndon Johnson from volume to volume is going to be sadly disappointed."

THE WEATHER OUTSIDE, as we walked along the margins of Central Park, was clear and bracing. Caro mentioned that he had been born a few blocks to the north, back in the days when this part of the Upper West Side was still more of a family neighborhood than an urban fortress for the well to do. His father, a Polish immigrant, was in real estate. "He was a man who found it difficult to express emotion," Caro once told Leo Seligsohn, of Newsday-which was more than I could get him to tell me. His mother died of cancer when he was a child.

"She took sick when I was very young," he said hurriedly, anxious to change the subject. "I remember that she loved to read. But I was very young, and she was very sick for a long time."

Caro attended Horace Mann, a private high school whose students came largely from a middle- or upper-class Jewish background, and then he went on to Princeton, where he wrote short stories of such length that one of them took up a whole issue of The Princeton Tiger.

After college, Caro worked as a reporter for the New Brunswick Daily Home News, in New Jersey, and served a brief stint as a speech writer and campaign director for a local political boss.

"I was making something like $52.50 a week as a reporter, and then I'd go in and write a press release for this guy, and he'd hand me a wad of fifty-dollar bills. On Election Day, I rode with him in his car, and at each polling place, a policeman would come up and report through the window about how they were doing and how they were keeping the other side-the reformers-from really supervising the election. I remember thinking, 'I don't want to be in here with you. I want to be out there with the reformers.' And so I just got out of the car. That was the moment when I began to realize who I really was."

It was at Newsday that Caro began to fully deploy his talents as a reporter and to sense their limitations. "Political power influences everybody's life," he told me. "I was writing about it every day, but I didn't really understand the truth about it. What I began to notice was that no matter what lines of investigation I chose to pursue, they allied to this guy Robert Moses. But nobody knew, including me, who the hell Robert Moses really was, where he got his power or authority from."

Caro decided to find out. From 1967 to 1974, he labored on his Pulitzer Prize winning study of a New York City parks commissioner who, through political genius and the abuse of public authority, became the most powerful figure in the state. If Robert Caro today is the very embodiment of writerly success-with a house in East Hampton, his own table at the Cafe des Artistes, and a comfortable income that is the product of hard-won literary prestige-during the years he was writing The Power Broker he was an impoverished former newspaper reporter with a tiny advance on the book, writing about a subject that every day grew more massive and uncontainable. To help finance the book, he and Ina ("My beloved idealist," he calls her in the acknowledgments to Means of Ascent) sold their house on Long Island and moved to Riverdale. When he finally finished The Power Broker, it was so long that 300,00 words (approximately twelve hundred manuscript pages, or three regular-sized books) had to be cut out of it.

"I really wanted to do a biography next about someone I thought I could love," Caro told me. "I was so angry at Robert Moses. He dispossessed five thousand people from one block-elderly Jewish people-to build the Cross-Bronx Expressway. When I interviewed these people, I'd ask them, 'What is your life like now? " And they'd say, 'Lonely.' And in my experience, that's a word people don't say unless it comes from deep inside. One evening I went to interview Moses and asked him if he thought these people were upset. He said, 'No, there's very little discomfort. It was a political thing that stirred up the animals there.' I wanted to punch him in the teeth."

Caro thought he would love Lyndon Johnson. He thought Johnson would turn out to be a shrewd, ruthless, but ultimately engaging populist like Al Smith. But that was before he found the dark thread.

Caro maintains that his portrait of Johnson is untainted by animosity, and it's true that no other writer has chronicled L.B.J.'s admirable traits-his devotion as a schoolteacher to his dirt-poor Hispanic students, his almost maniacal responsiveness to his congressional constituents, his truly heroic indifference to exhaustion and physical pain in the 1948 campaign-with anything approaching Caro's precision and fervor. But it would be pointless to pretend that Caro is a cool scholar. He reports on Johnson's villainy with an undertone of personal offense.

"When I found out how he betrayed Sam Rayburn, I was almost indescribably sad," he told me, referring to the way Johnson had cruelly usurped Rayburn's role as President Roosevelt's most-favored Texan. "Part of my feeling about Rayburn was how lonely he was, and how much he needed Lyndon and Lady Bird. I was sitting there in the Lyndon Johnson Library, reading these telegrams and memos back and forth to Washington. And I suddenly began to see what was happening. I remember I got up from the desk with a horrible feeling. I'm sitting there taking notes, and it's about to happen. Johnson is about to betray this man who loved him. I went outside the library and walked around it several times and thought, 'God, don't let this mean what I think it means.' I didn't want this to happen to Rayburn."

But if Caro was outraged by Johnson, he found a hero in Coke Stevenson. In Means of Ascent, Caro introduces the cowboy governor in a long chapter entitled, with the simplicity of a children's fairytale, "The Story of Coke Stevenson." What follows is a beguiling but controversial portrait in which Stevenson, in contrast to Johnson's Black Bart, is presented as the last great hero of the Old West. A check of the book's index reveals in a glance how the author has set the stage. Under "Johnson, character of," there is a preponderance of such entries as "aggressiveness," "ambition," "cruelty," "cynicism," and "flattery and obsequiousness." Under "Stevenson, character of," one finds "dignity," "fairness," "frugality," "honesty and integrity," "sense of humor," and "sincerity."

"All I knew about Coke Stevenson," Caro said, "was that he was the guy who lost in 1948. I had no intention of writing about him in detail. Then one day I was interviewing a congressman named Wingate Lewis who had been in Fort Worth in the forties and fifties. He was an extremely pragmatic, cynical politician. He was explaining to me that he had been afraid of Johnson's power because Johnson was so close to his principal supporters. He said something to the effect of 'I even had to support Lyndon against Coke Stevenson in 1948.' Then he said-and remember that this was a very pragmatic man-'I knew Coke Stevenson, and I thought a lot of him. He lived by the code of honesty.' Well, to have come out of his mouth words like that about a governor who lived by the 'code of honesty' sunk into my consciousness. And I heard the same thing from other people-and I realized they were speaking of Stevenson intones of reverence."

Not everyone, though, speaks of Stevenson in those tones, and Caro's portrait has drawn fire from critics who remember Stevenson as much for his racial bigotry (a topic that Caro mentions only glancingly) as for his political integrity. ("The problem with Caro's method," says Lewis Gould, a historian at the University of Texas, "is that the same standard that is so rigorous and difficult for Johnson to meet is sort of put aside for someone Caro admires.")

If Steyenson was so great, I asked Caro, why do so few contemporary Texans seem to be aware of it?

"It's totally lost! The last guys who knew him are dying as I write. Texas is a state with a history that's not only truly glorious but truly significant in understanding America. And I think Texas is losing that history. For instance, Stevenson was a conservative, and we've forgotten what that meant. We see conservatism today in a form in which one of its original, motivating, particularly American impulses has just about totally vanished. What's vanished is the spirit of the frontier individualism and self-reliance that imbued conservatism with something noble and heroic.

"The most amazing thing that's happened to me in my writing career is the reaction to Coke Stevenson. Not in Texas, but in New York. After The New Yorker excerpt came out, one of New York's most glamorous hostesses called me and said, 'My God, I gave a dinner party Saturday night, and all I heard about was Coke Stevenson.

The literary world in New York is all talking about Coke Stevenson!' "

I was beginning to sense that Caro was going to catch some flak in Texas over this one. Part of it, of course, had to do with sheer provincial envy, the realization that it had taken a Yankee from Central Park West to render Texan culture with such enduring authority. And part of it was the uneasy and wary feeling that New York was now the arbiter of Texas's heroes. Lyndon Johnson, whom Texans used to rather like, had been expertly dismantled before our eyes, and now in the salons of Manhattan the latest intellectual fashion threatened to be frontier conservatism.

ROBERT CARO WRITES his books on the tenth floor of an office building near Columbus Circle. As a point of discipline, he works in a coat and tie, even though he is there all alone, the telephone turned off, the mail slot closed-nothing to distract him from the daily task of reconstituting the life of Lyndon Johnson.

When I walked up to his office, I noticed that Caro has a gold-colored nameplate on his door, just like those of the dentists and talent agents in the other offices. Inside, Caro's workplace was a model of idiosyncratic organization. Instead of the unruly pile of notes and books one would expect of a biographer, there was a big, clean desk without a sheet of paper on it, just a portable electric typewriter and a lamp whose base was a bronze statuette of Apollo in a horse-drawn chariot. One wall of the room was lined with bookshelves and files, and just above the desk hung a large corkboard displaying the twenty or thirty sheets of paper that form his outline.

The outline is the key to Caro's working method. "I'm determined to think through the book from beginning to end before I start it," he told me. .'First I make a very short outline, just a page or two. Then I start filling it in with transitional sentences and key thoughts. You're really writing the book without the details at that stage. Then what I do is I go through the notes and fill in the details. Let's say I have a hundred and fifty pages of notes dealing with a particular incident-but of course I don't; I have nearly a thousand. Anyway, you give a number to each interview. You go through all your file folders, and you index everything in it to that outline. And the outline keeps growing until you've got the entire book-an entire wall, twenty or thirty feet long, covered with paper. There it is. And then you come in one day, and you look at it, and you have to start writing."

But between the sheets of paper on the wall and the actual writing is an even more detailed outline, one chapter at a time, that he keeps in a three-ring binder. This outline has notations indexed in red markers to corresponding numbers in the file cabinets. The other tools of his trade are black ballpoint pens and white-not yellow-narrow-lined legal pads, a product, he notes with some alarm, that is being discontinued. Caro doesn't use a computer, or even, for the first few drafts, his typewriter. He writes in longhand to slow himself down.

“I don't know how good a writer I am," he confided as he leafed through a stack of notes that he had transcribed from his sui generis shorthand. (He almost never uses a tape recorder.) But I'm a very good interviewer. I tried to learn how to interview from two characters in fiction. One is Inspector Maigret and one is George Smiley. When I was a reporter, I felt I was too aggressive in asking questions. The thing about both of them is that they're quiet and patient. They let the other person talk and really listen to what he's saying. Maigret takes out his pipe and refills it and taps it on the table. Smiley takes his glasses off and wipes them on his necktie. It's a way of keeping themselves quiet. I write 'shut up' in my notebook a lot. Or just 's.u.' If you looked through my notebooks, you'd see a lot of s.u.s."

Caro picked up a neatly folded sweater and slipped it on. For the first time, I thought I could detect a trace of weariness in him, and I thought of the twenty-five remaining years of Johnson's life that still faced him-the rise to power in the Senate, civil rights, the Kennedys, the vice presidency, the assassination, Vietnam, the brief twilight years at his ranch on the Pedernales River. It seemed more than two volumes of narrative, and it seemed a bit more than one biographer's lifetime.

Did he ever worry, I asked, that he would grow old and die before it was finished?

"I try not to think about that," Caro said. "I don't like to feel rushed."