This article originally appeared in VANITY FAIR April 1990 and is reprinted with permission of NICHOLAS VON HOFFMAN and the photographs are reprinted with the permission of JONATHAN BECKER.

Robert Caro's Holy Fire

The first volume of Robert Caro's epic life of Lyndon Johnson was both a definitive act of scholarship and a journalistic sensation. The long-awaited publication this month of volume two, Means of Ascent, proves once again that Caro is a newsmaker and a history breaker: NICHOLAS VON HOFFMAN reports on the man who's going all the way with L.B.J.

For years the question in the publishing industry , in the state of Texas, and among serious readers everywhere was: When is volume two going to be printed? It got so you had only to say "Have you heard anything about volume two?" and people knew what you were talking about without your mentioning Robert Caro's name.

Volume one, The Path to Power, is the

beginning of Caro's epochal biography of America's thirty-sixth president, that

stentorian, grab-ass son of the Texas Hill Country, Lyndon Baines Johnson. What made it both a critical success and a big best-seller was its admixture of two things which seldom go

together, sensationalism and immaculate scholarship.

The lives of other modern presidents are given to us by

droopy-drawered academics. To this day, to form a full picture of John F. Kennedy, the man who preceded Johnson into the White House, we have to rely on accounts not from his professor biographers but from the sycophants

who's serviced him. So when Caro's volume one appeared, with its startlingly accurate and detailed narration of this mendacious man's early life-his mistress, his stealing elections in college and blackmailing a fellow student, his having uncomplimentary references to himself physically cut out of hundreds of copies of his class year-book-people couldn't wait for more. They had to, for eight years. Only now is volume two being published, but Means of Ascent was worth waiting for.

Critics may complain of Caro's malice toward his subject, but if the book seems loaded against Johnson, it is because much of the unflattering material about his lying, his

political brutality, and his use of power for personal gain is so new. It is new, Caro points out, not because it was so deeply hidden but because journalists didn't look for it, or when they did look, as with the vote stealing, the more influential political public was disposed to chalk it up to the quaint way they did politics down there in Texas.

Robert Caro isn't out to get Johnson, nor is he obsessed by the man. "Abraham Lincoln struck off the chains of black Americans," he writes, "but it was Lyndon Johnson who led them into voting booths, closed democracy's sacred

curtain behind them...made them, at last and forever, a true part of American political life."

Nonetheless, it is hard for some people to understand how a man can spend so many years and so much concentration on a single subject. To which Caro says, "Why does it take so long? I really want to take the time to find out what happened, and time equals truth. I hated being a reporter , because you never had enough time...I'm not obsessed with Lyndon Johnson. I'm interested in how power works in a democracy."

This has always been the theme of Caro's writing. As a young reporter, he came to believe

that "the essence of power is not what we're taught in political science, and I began to understand it was important that we understand this force

which shapes our lives." His first book, about Robert Moses, New York's public-works-development emperor, was a

study of power at the local level; the Johnson biography examines power at the national level.

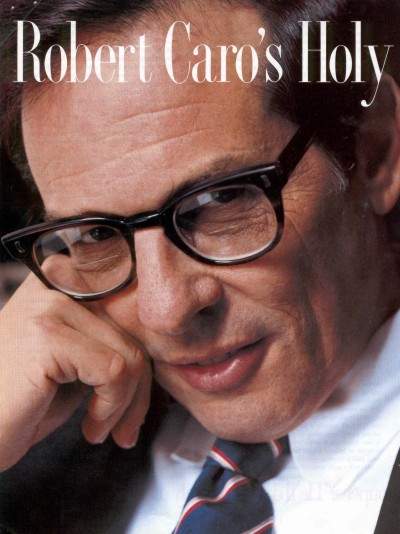

The picture of Robert Caro on the back of volume one made him look Clark Kentish. Now that he's in his fifties, the real man and the comic-book hero look less alike. But publication of volume two of the biography has proved that the mild-mannered Caro, even if he doesn't sport blue underwear beneath his business suit, remains the super-reporter, of his time.

Unlike supermen, super-reporters have their limits. So the book does not reveal if Lady Bird Johnson,

Lyndon's somewhat plain, somewhat dumpy wife, knew about gorgeous Alice Glass, who was Johnson's mistress as well as

the mistress of Longlea, her Virginia hunt-country estate. Caro says that when Lady Bird, heard that he had gotten onto the long-smothered Alice

Glass connection she invited him to the ranch and talked about the other woman in the

most flattering terms. That was the moment to ask her whether she knew, but Caro

admits, "It was the only time

in my life that I was too embarrassed to ask a question. I couldn't ask a single

question...Nor do I understand to this day why she made those statements."

If Johnson, elephant-eared, trumpet-mouthed, arms flailing, is frighteningly present in

this book, Lady Bird is movingly so. Shy past the point of self-abnegation, she comes

across as one of those Civil War-era southern women who were reared to do nothing and know nothing, but who, leg- end has it, could take hold of the plantation when the men- folk were off at war and-by God and Harry!-run it well. When Lyndon Johnson, a young congressman, went off to World War II, he ordered her to take over his political

business, and Lady Bird, who knew nothing about politics and nothing about government, forced herself through doubt and crippling insecurity to learn how to call the mighty of the land on the telephone and to confront them face-to-face in order to get what she needed for Lyndon's constituents.

She ran the plantation as well as he had, but by her own methods, and when he came marching home from a combat career he exaggerated for years afterward, she stepped back into the shadows to love, honor, and obey him while he yelled at her in public, ordered her around, and deprecated her in front of other people. In case somebody got the idea Lady Bird was special as a helpmate and adviser, Lyndon set 'em straight:

"I talk everything over with her...of course, I talk my problems over with a lot of people. I have a maid, and I talk my problems over. with her too."

Caro describes Lady Bird so well that the reader feels he is living through the humiliations visited on her by a husband who, in the book at least, almost never does a tender, loving, or even considerate thing for this woman. Caro is convinced she loved him fully and completely anyway, but he also says, "I'm glad I'm writing about Lyndon Johnson and not Lady Bird Johnson, because I don't understand

her...The saddest thing was I knew this book was going to hurt her. I don't like to hurt people. I wish it could have come out differently."

To meet Caro is to know he is a kind man, impatient perhaps, but one who doesn't like causing pain. The ultimate investigative reporter, he has none of the steamy

prosecutorial zeal and bad manners said to be the hallmarks of the effective adversarial journalist. In the stories he spins, there are no anonymous Deep Throats, no unnamed sources. The

crimes and misdemeanors laid out in Means of Ascent are not merely confessed but

explained and analyzed by the men who committed them. The couriers carrying the money remember the night

flights to Austin with bundles of cash in brown paper bags. They remember the time John

Connally absentmindedly left $50,000 (a quarter of a million in today's currency) in $100, bills in the Longhorn Cafe,

where they'd stopped for a bite to eat.

And despite the fact that Caro is a polite man, soft

of speech, attentive, and private, he gets interviews from people who never, ever, talk.

Compare Means of Ascent with Lincoln Steffens's early-twentieth-century classic, The Shame of the Cities. The political malefactors in Steffens's pioneering book told him little and elaborated on that little with the scantiest details. Contrast that with what Caro found out about Brown & Root,

the gigantic, worldwide contracting company: he lays out, dollar by dollar, how Herman Brown and Lyndon Johnson and their circle of : corruptionists stuffed ballot boxes and stole elections, and

how Brown's questionable contributions to Lyndon Johnson's campaigns were converted into hundreds of millions, of dollars' worth of government business.

"I

could never have written the Brown & Root part without [Herman's brother] George Brown. No one else knew it...George Brown never talked to anybody. He boasted he'd never given an interview about his brother. I didn't know what to do to get him to talk,"

Caro recalls.

For years he tried over and over to get to George Brown; he tried directly and indirectly through Brown's confederates who had become friends of Caro's

in the course of his research. One thing he did know about George Brown was that he had

idolized his dead older brother, the founder and driving force behind Brown & Root. George spent millions to bedeck the state of Texas with buildings which had Her- man's name chiseled on them. Caro was looking at one such edifice, a Herman Brown Public Library in some small Tex- as town, when he had the idea that got him the interview.

Through an intermediary , he sent a message to George: "No matter how many buildings you build, no one is going to know who your brother was if he isn't explained in a book." The next morning Brown's secretary called.

When Caro had made himself comfortable in George Brown's office, he didn't start by asking about political

contributions. He asked about the beginnings of the Brown & Root empire. Brown

searched among the things on his desk to find an ancient, rusty pulley, a memento from the first dam the Brown brothers had built. "Picture," Caro says, "this very old, almost blind guy telling this story that had never been told before...It was quite wonderful." Wonderful too for the reader, who is given a unique account of the erection of a multibillion-dollar

enterprise through the carburetion of government and politics. Before the New Deal, such things rarely happened; from the New Deal on, they became the norm, as shown by the recent conviction of two

congressmen in the Wedtech scandal.

When John Connally, whose involvement in the politics of both parties has gone from being Lyndon

Johnson's right-hand man to being Richiard Nixon's secretary of the Treasury,

talked to Caro, it made headlines in Texas. For years Caro had tried to reach

Connally, but hadn't gotten a peep in reply.

Then a friend called Caro to exclaim, "I was at a party last night and Connally was there and he's reading your book [volume one]! He loves it!" It turns out that the pompous, blowhard Connally, the yahoo Texas gasbag we see on television, is a night-and-day reader, a brilliant and studious man. "You know within a minute of meeting him why Richard Nixon was so impressed with him," says Caro. Volume one won Caro a free flight on Connally's private plane to his ranch, and a four-day-and-night ,interview with Johnson's closest confidant. It yielded an eyewitness account of exactly how Johnson got on the Kennedy ticket in 1960, and laughing confirmation of the story that Connally thought he had lost $40,000 in cash campaign contributions in his laundry and then, after checking every cleaning establishment in Austin, found it among his shirts.

It works the other way, too. People who have been talking back off. Lady Bird Johnson dropped the gate after a

series of interviews for which she had carefully prepared by looking through old logs and appointment books to freshen her memory. At first, Caro believes, "the Johnson people saw this as their passport back to respectability,

but then the time of helpfulness ended. Caro guesses he knows why. Before volume one was

published he chanced to see a picture in a Texas newspaper of a gathering attended by four or five of his sources, each one of whom had been "telling me what he wanted me to know."

He could imagine each of these men recounting to the others what he had said to Caro until one of them exclaimed, Holy shit, he knows the whole story! "All I know is the next week the phone stopped ringing...It was as if the word went out."

Once the statute of limitations has run out, however, men often want to talk for history.

It was this motive that moved rich and secretive fixers as well as the poor Mexican-American precinct worker who stole the eighty-eight votes which put Lyndon Johnson into the Senate and on the highroad to the presidency. But just because they talk to you doesn't mean they're telling the truth. Johnson's brother lied to Caro. "Sam Houston Johnson drank a lot," Caro recalls. "He also talked with a bravado that made you

rather distrustful of what he said...I decided not to use anything he told me."

Then, several years later, he ran into Sam Houston again, now off the sauce and, after an operation, calmer, more

serious, even religious. On a hunch Caro took him to the Johnson homestead, sat I him down at the dining-room table, and said, "I want you to

recreate for me one of those terrible arguments that your father used to have at this table with Lyndon."

"At first," Caro recalls, "it was very slow going. But gradually the inhibitions, fell away...He started talking faster and faster...By this time I felt that he was really in the frame of mind to remember accurately, and I said,

'Now, Sam Houston, I want you to tell me all the stories about your brother's boyhood that you told me before, the stories that your

brother told all those years, only give more details.' There was a long pause. Then he said, 'I can't.' I said, 'Why not?' And he

said, 'Because they never happened.'"

Bagging the big interview doesn't suffice to explain how Robert Caro has changed the art of political biography. "His research is inexorable," says Bob Gottlieb, his editor of eighteen

years, Caro has tracked down every living member of Johnson's grammar-school class,

and sniffed out every connection to the third, fourth, and even fifth degree.

And there is another class of interviewees in Caro's books, people who never met the books' subject and had no effect

on him but were affected by him. "History," Caro says repeatedly, "isn't history unless you show the effects of power. You have to go both ways or you don't have history... My concept is to show how power works and how it affects all our lives." To that end he intends, when he gets to that point in his work, to find a village in Vietnam picked for bombing by President Johnson.

"I want to find one of the bombing targets he selected and go live there."

Caro's friend historian Robert Massie, knowing Caro's fastidious tastes in food and dress, has doubts about how this is going to work out. Nevertheless,

Caro, who can be found dining at chic Manhattan restaurants like Cafe des Artistes and

Elaine's, took a sandwich and a sleeping bag to camp out at a spot near the Johnson's

ranch in the Texas Hill Country. He seeks to endow his work with the pungent "sense of place" he experienced in

reading Francis Parkman, the nineteenth-century American historian, and years ago, when he and his wife moved to Texas to undertake this work which will use up the rest of his life before the last of the

contemplated four volumes is written, a woman who knew the president from his earliest years told Caro, "You'll never. I

understand Lyndon Johnson if you don't understand the land-living in that land made you so ruthless."

"When I was interviewing Johnson's brother, Sam Houston," Caro says, "a word that kept coming up was 'lonely.'"

Lonely in Hill Country, Caro found out, was "when you are so alone even the flash of a rabbit's tail is a big event." As

he describes the terrain in volume one, "there was nothing...no movement except for the ripple of the leaves in the

scattered trees, no sound except for the f constant whisper of the wind, unless, by

happy chance, crows were cawing somewhere nearby." It was "an endless vista

of hills, hills on which there was visible not a single house...hills on which

nothing moved, empty hills with, above them, empty sky; a hawk circling silently high overhead was an event. But most

all, there was nothing human, no one to talk to."

Caro's story of Johnson-already

defeated in one race for the U.S. Senate, running a second time, and knowing if he

loses again it's curtains for his political career-is equally indelible: it's an

anatomy of a pathological winner looking at the annihilation of defeat and ready to give up

health, even life itself, to escape losing. Here is a man continuing his twenty-hour-a-day campaign while suffering a life- threatening kidney-stone attack, feverish

to the point of delirium, bent over in pain, smiling and waving when the voters can see him, vomiting when he's out of their sight.

The description of the future president 1 racing across Texas in a Pullman car with

a young aide, Warren Woodward, is beyond melodrama:

Woodward's lower berth was directly across from Johnson's, and neither man got much sleep. By this time, his temperature soaring ...Johnson would shout across the aisle, "Woody!" Jumping up, in his pajamas, Woodward would cross the aisle, and open the curtains of Johnson's berth. "Get this window open!" Johnson would say, and Woodward would see sweat pouring off him from his fever. "Finally," Woodward

recalls, "the fever would pass and he'd maybe doze off for a little bit." Woodward would close the window. Then a chill would come. The chills were very bad: "He was just shaking uncontrollably." Woodward got the porter to collect all his spare blankets and pile them on Johnson, but they didn't help. "I'm freezing, Woody! I'm freezing!" Johnson would cry. He asked Woodward to get into bed with him; and Woodward did, and wrapped his arms around

him "to try to give some heat from my body over to his and try to keep him warm."

An undertaking like the Johnson project is best carried out by a man with a maniacal self-absorption. It is well that

Caro is as lovable as he obviously is, because even a stranger can intuit that this is

not an easy man to be around a lot of the time. He admits to having quite a temper,

and when you see him in his habitat, his extremely ordered, indeed perfectly neat "home, you think this is a man who must

have all about him as he wants it. Yet he wrote much of The Power Broker with a

little bird perched on his shoulder next to his ear. His son had found the cedar-wax-wing chick after its mother had been

killed, and brought it home, where the Caro family fed it Pablum every few hours

until it grew up, evidently under the impression that Bob was its waxwing daddy.

It is also well that he is so completely

organized, for Bob Caro does it the old-fashioned way: he writes everything out in

longhand, and the tens of thousands of records of interviews and documents

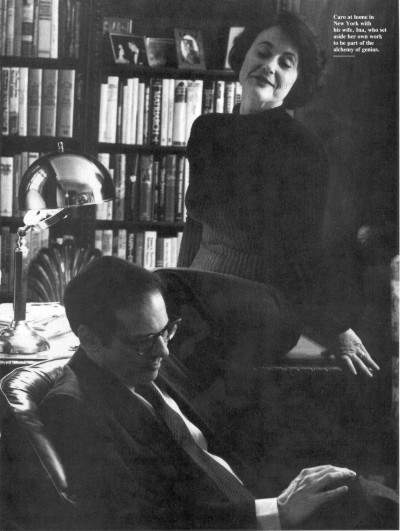

needed for his work are stored and indexed with no help from most researchers' best friend, the computerized data bank. But even he could not have perused so many documents and talked to so many hundreds of people without someone's help. That help came from his wife, Ina.

In this era of divorce, there are certain couples whose devotion to each other is almost as important to their friends as to the couple itself. The Caros have such a marriage. They were married when Bob graduated from Princeton and Ina was still attending Connecticut College for

Women. Thirty-two years later, their son having grown up, they are closer than ever. Their research is so daunting that you come to think of them as a couple of

human bullets describing an undeviating line toward the truth, but in fact they are a sociable couple. Their New Year's Eve parties are an institution in their circle, they have a house on Long Island, and for thirty years they've had season tickets to New York Giants football games.

When their friends want to indicate what this marriage is like, they

talk about the fiftieth-birthday party Bob gave Ina at the Century Club. Bob, who is something of a foodie, not only supervised all the preparations but rehearsed each guest's toast to Ina. No portly, slightly tipsy

fellows hauling themselves to their feet to speak whatever words are prompted by the grape. If this seems a trifle too-too, the fact remains you cannot understand how these remarkable books were made if you don't take into account the

relationship between the Caros.

Ina is a trained historian in her own right, whose proper field was the

European Middle Ages. When her husband first asked for her help she was buried in the New York Public Library, translating what she

calls, "a mass of horribleness" , from Latin into English. At the time, Caro was working on his first book, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (Knopf, 1974). He had just injured his back playing basketball and would be confined to his bed for a year, during

which time he needed someone to do some work in the Nassau County courthouse.

Ina would go out to Mineola, Long

Island, with a purse full of change for the phone, get instructions "to go to row such

and such and pull out a volume. Then I would call him and tell him what I found." Bob, who as a reporter for

Newsday had memorized the courthouse, had no trouble directing Ina to the right places.

At one point during the seven years the Moses book was in preparation, Ina was pressed into service as the driver of a

get-away car. Caro wanted to look at the effects of power as wielded by New York's planning-and-construction dictator. So he spent half a year finding and interviewing the people whose lives had been disrupted by one mile of one of

Moses' roads, the Cross-Bronx Expressway. This section of the central Bronx had become a

howling slum since the landscapers and wrecking balls had eradicated the heart of the community.

Twenty years later the memories of the urine-permeated halls, the children' s faces, and what lay behind those

apartment doors are fresh for Caro. For a middle-class researcher it was an intimidating place to be sloshing around in. While Bob went interviewing, Ina would sit in the locked car protected by Wags, the family dog, who, she says, was "a real

yapper." Once, Wags had cause to yap in earnest as Bob, on the rabbit end of a chase, came running and leapt into the car as Ina

gunned them out of there.

Medievalist that she was, Ina says, "I

had never interviewed a person, never really been in contact with the present,

century." So it was "like blasting me out" when Bob told her, "You've got to

get out of the library" and talk to real people. They were working on the first

volume of the Johnson book and Ina recalls that Caro "wanted to prove once and

for all whether the federal government could truly help people who couldn't help

themselves because of circumstances beyond their control." The test would be the

electrification of the Hill Country, which Lyndon Johnson had worked to bring about. The standard biographies shed no

light on the subject, so Ina drew up a list of the farm families who had been in

Johnson's Tenth Congressional District at the time, and, nerves ajangle, set out for the home of Mr. and Mrs. Curtis Cox. The Coxes were just as nervous about

being interviewed as Ina was about interviewing, but they received her with that

kindness which seems special to country people everywhere. They had roasted a goat and made peach ice cream. Ina was

on her way to becoming an expert on rural, electrification and farming practices;

today, Robert says, "Ina knows more about contour plowing than any other woman

on Central Park West."

Some of Ina's women friends may think that she has given too much for Bob's work, but Ina, now writing a book of her own, disagrees. She sees herself as part of the alchemy of genius. The result of Ina's work on rural electrification was one of the most moving parts of volume one, the description of young congress- man Johnson's bringing electricity to the Texas Hill Country in the late 1930s. "I cried when I read it," Ina recalls. "You can't imagine how boring the material was that he took. If you saw the material he took it from-it's magic. I've so

enjoyed working for him." Caro has recreated what life on those isolated,

upcountry dry farms was like before there was light. People told him, "We loved Lyndon because he brought us the

lights."

Caro has been criticized for the

discursive breadth of his work, for incorporating long sections on such things as rural electrification, but he almost has to write his Proustian

form of biography in order for his subject to be understood. The title of many a biography reads, The Life and Times of So-and-So, but it's only the life; the times aren't there. Fifty years after the fact only octogenarians can have a

realistic appreciation of what a New Deal pro- gram such as rural electrification meant to the millions cut off from lights, radios, electric water pumps, and washing

machines on the distant farmlands of the time. To people under forty, New Deal is another way of saying bureaucracy, waste, and sloth. Without these

extended asides it is impossible to write a comprehensible life of a figure like Lyndon Johnson.

In addition to being obliged to make up in his own books for the general histories which aren't being written, Caro has had to break new ground. At the time Caro began his work on Moses, a man who governed millions of people without ever holding elective office, no book on the subject of public authorities had been published, although the great shift of power from elective to

non-elective politics had been under way in America for some years.

Bob Gottlieb says that the uncut

manuscript of The Power Broker ran to 1.1 million words. Only pedants, which Caro decidedly is not, or people animated by a holy fire turn in works of that length. Originally the book had been with a

different editor at a different house, which had paid Caro a $2,500 advance for a book he thought it would take nine

months to complete. Flat broke and five years into the project, he submitted the first 400,000 or 500,000 words in hopes

of getting a second $2,500 payment, due on completion. His editor took him out to a cheap Chinese restaurant at the comer of

1O7th and Broadway, as Caro remembers that unhappy evening, and told him that while the people at the office thought he was writing "one of the most important works of nonfiction in the twentieth

century" they were "not prepared to go beyond the terms of the contract."

At this point the Caros had sold their house and used up the proceeds to finance the book. "The worst was that I

didn't know what to say to Ina," says Caro, who remembers walking "in a daze" up Broadway to the island's end and home to the Bronx. But Ina never had any doubts, and no one who read that manuscript ever had a doubt, either.

The Power Broker won a Pulitzer Prize. Now in its twelfth printing, it is required reading in university courses. Robert

Kiley, chairman of New York's Metropolitan Transportation Authority and a

pluperfect example of the modem non-elective politician, points out that Caro's work has been a lesson book for a generation of

Kiley's peers. Unfortunately, where Caro led, few have chosen to follow: since The Power Broker, we've not had many new portraits of this kind of politician who, from J. Edgar Hoover and Douglas Dillon to former surgeon general C. Everett Koop, now dominates American

government at all levels.

Power and democracy are high-level abstractions. It was, however, concrete events that gave those words

emotional force for Robert Caro. "The pivotal day in my life as a young reporter," Caro recalls, was when he was covering the state capitol in Albany. There was a

proposal to build a bridge across Long Island Sound, a project which virtually no one favored, because it would increase

pollution and congestion. But, Caro remembers, the news was whispered through the capitol that Robert Moses was there, and

"the next thing I knew everybody from the governor on down was for the bridge. I saw I didn't know how anything works."

Caro' s vocation had begun to take form even earlier, during his first job, on a New Jersey paper, the New Brunswick Daily Home News. This young

man, with his white-bread upbringing and prep-school/ Ivy League education, was pushed in to cover a local campaign while the regular political reporter was on leave. The

custom was for the reporter on that assignment to make a little money on the side by writing a few speeches.

'The local leader," as Caro tells it, "took a real shine to me, and I loved the feeling of being on the inside, of walking out on the stage with the politicians."

Election Day came and Caro was with the leader in a car driven by a police captain as they went from

polling place to polling place. When they stopped, uniformed policemen would report through the window about "doing the little things to discourage the voters.

Suddenly I said to myself, I don't belong on the inside. I got out of the car. I quit the leader and the newspaper."

The great journalists and historians are always outsiders, and they are always, at bottom, angry.

Caro felt that anger when he interviewed three couples who had been uprooted by that mile of the Cross-Bronx Expressway. He was asking them what their lives, post-demolition, were like, and

"I remember hearing again and again: 'lonely.' That's the one word nobody lies about, and I knew that that road didn't have to go there, that it went there because of a deal with the Bronx political machine."

Later the same day, he had an interview with Moses, who was serving drinks and being as charming as he could be when he wanted. Caro brought up the lonely

refugee couples, to which Moses responded with the phrase "Just stirring up the

animals." Caro felt the flush of rage-and the conviction that the world had to know about this man.

"You get so angry. The injustice that these people can do."

The flush came on Caro again when he was working on this second volume of the Johnson biography and beheld his subject

"stealing thousands and thousands of votes...We think we know what elections are. Nobody knows what an election is like. Nobody knows how dirty they are.

Nobody knows! Shouldn't we know it?"